- Written by Jan McKenzie

- Seoul correspondent

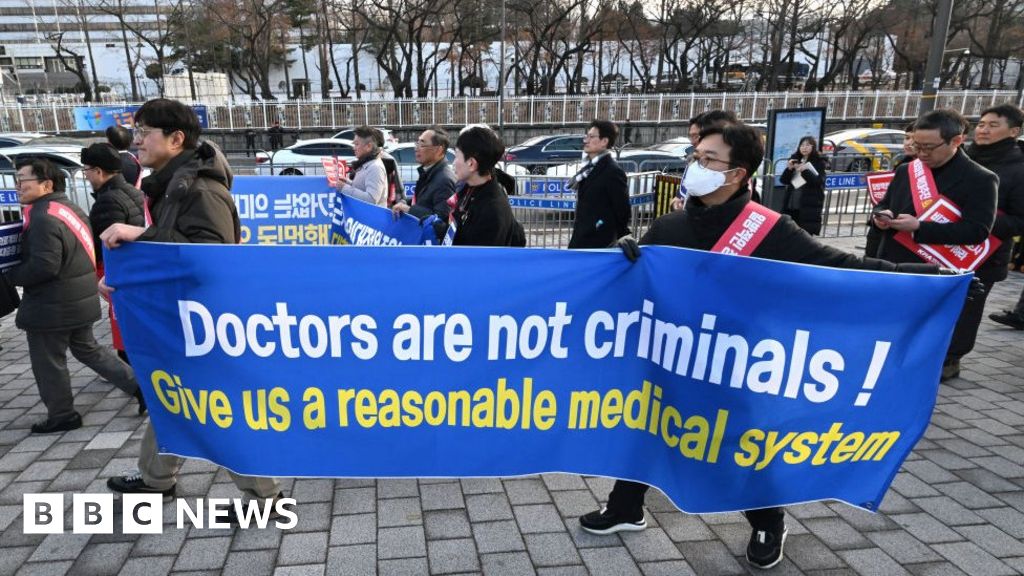

South Korean doctors protest the government's medical policy in front of the presidential office in Seoul

The South Korean government has threatened to arrest thousands of striking junior doctors and revoke their medical licenses if they do not return to work on Thursday.

About three-quarters of the country's junior doctors have left their jobs over the past week, causing disruption and delays to surgeries at major teaching hospitals.

Trainee doctors are protesting against government plans to admit more medical students to the university each year, to increase the number of doctors in the system.

South Korea has one of the lowest doctor-to-patient ratios among developed countries, and with a rapidly aging population, the government warns there will be a severe shortage within a decade.

Empty hallways at St. Mary's Hospital in Seoul this week gave a glimpse of what that future might look like. There was barely a doctor or patient to be seen in the triage area outside the emergency room, with patients warned to stay away.

Ryu Ok Hada, a 25-year-old doctor, and his colleagues have not gone to work at the hospital in more than a week.

“It's a weird feeling not waking up at 4 a.m.,” Rio joked. The junior doctor told the BBC that he used to work more than 100 hours a week, often for 40 hours without sleep. “It's crazy how much we work for such little pay.”

Although salaries for doctors in South Korea are relatively high, Ryu says that due to their working hours, he and other junior doctors may end up earning less than the minimum wage. He says more doctors will not fix structural problems within the health care system, leaving them overworked and underpaid.

Healthcare in South Korea is largely privatized but affordable. Doctors say prices for emergency, life-saving surgeries and specialist care are very low, while less important treatments, such as cosmetic surgeries, pay too much. This means that doctors are increasingly choosing to work in more lucrative fields in big cities, leaving rural areas understaffed and emergency rooms overstretched.

Ryu Ok Hada, a doctor at St. Mary's Hospital, has not gone to work in more than a week

Rio, who has been working for a year, says trainee and junior doctors are being exploited by university hospitals because of their cheap labour. In some major hospitals, they make up more than 40% of staff, providing a critical role in their continued employment.

As a result, surgical capacity in some hospitals has been cut by half over the past week. Disruption was mostly limited to planned procedures, which were postponed, with only a small number of isolated critical care cases affected. Last Friday, an elderly woman who suffered a cardiac arrest died in an ambulance after seven hospitals refused to treat her.

“There are no doctors”

Patience with doctors is wearing thin on both the public and healthcare workers who need to put up with the extra work. Nurses have warned that they are forced to carry out procedures in operating rooms that would normally fall to their fellow doctors.

Choi, a nurse at a Seoul hospital, told the BBC that her work shifts had been extended by an hour and a half each day, and that she was now doing the work of two people.

“Patients are worried, and I feel frustrated that this continues with no end in sight,” she said, urging doctors to get back to work and find another way to air their complaints.

Under the government's proposals, the number of medical students accepted into university next year will rise from 3,000 to 5,000. The striking doctors claim that training more doctors would weaken the quality of healthcare, because it would mean granting medical licenses to less qualified practitioners.

But doctors struggle to convince the public that more doctors would be a bad thing, and they have received little sympathy. At Severance Hospital in Seoul on Tuesday, 74-year-old Ms Lee was receiving treatment for colon cancer, after traveling more than an hour to get there.

“Outside the city where we live, there are no doctors,” she said.

“This problem has been on the road for too long and needs to be solved,” Lee Soon Dong's husband said. “Doctors are very selfish. They take us patients hostage.”

The couple were concerned about more doctors joining the strike, and said they would be happy to pay more for their care if it meant resolving the dispute.

But President Yoon Suk-yeol's approval ratings have improved since the strike began, meaning the government has little incentive to start reforming the system and making the measures more costly, before elections scheduled for April.

Both sides are now locked in an intense confrontation. The Ministry of Health refused to accept the doctors' resignations and instead threatened to arrest them for violating the medical law if they did not return to hospitals by the end of the day. Those who miss the deadline will also have their licenses suspended for a period of at least three months, Vice Health Minister Park Min-soo said.

Although some of those who have withdrawn believe the government's hardline approach may change public opinion. On Sunday, the Korean Medical Association will vote on whether senior doctors should join trainee doctors. If a large number of their younger colleagues are caught, they are more likely to take action.

Ryu said he is prepared to be arrested and lose his medical license, and if the government does not compromise or listen to their complaints, he will walk away from the profession.

“The medical system is broken, and if things continue like this, it will have no future and will collapse,” he said. “I've done some farming before, so maybe I can get back to that.”

Additional reporting by Jake Kwon

“Infuriatingly humble alcohol fanatic. Unapologetic beer practitioner. Analyst.”

More Stories

The United States is close to completing the construction of a $320 million floating dock to aid Gaza

Brazil floods: People stranded on rooftops in Rio Grande do Sul

BBC on board a boat chased by China in the South China Sea